Through photosynthesis, it can be said that the whole world runs on sugar! See how organic matter is the glue that holds soil together through the demonstration of a Slake Test.

Growing Our Capacity for Good Work: A Stockmanship Clinic with Marissa Taylor

09/27/2023

By: Mukethe Kawinzi

Our livestock are at the core of our approach to rangeland management: their grazing and movements spur the process of regeneration. Their continual well-being is paramount; we believe that raising good meat and working in concert with nature requires us to understand and communicate with our animals on their terms. The idea of stockmanship, developed by Bud Williams and further formalized by Whit Hibbard, allows us the knowledge and ability to handle our cattle and goats with compassion, efficiency, and safety.

Our livestock are at the core of our approach to rangeland management: their grazing and movements spur the process of regeneration. Their continual well-being is paramount; we believe that raising good meat and working in concert with nature requires us to understand and communicate with our animals on their terms. The idea of stockmanship, developed by Bud Williams and further formalized by Whit Hibbard, allows us the knowledge and ability to handle our cattle and goats with compassion, efficiency, and safety.

This September, Marissa Taylor of Lonetree Ranch in Wyoming, led a two-day workshop at TomKat Ranch on stockmanship. A group of women livestock managers—herders, shearers, ranchers, and farmers—came together for the inaugural skill-building clinic from Women in Ranching. There, Taylor shared her collected notes on proper, that is, low-stress livestock handling. After years of training and study, she has synthesized work from the field with her own experiences to build a philosophy of working animals.

Hibbard’s working definition of stockmanship is: The knowledgeable and skillful handling of livestock in a safe, efficient, effective, and low-stress manner. Stockmanship denotes a low-stress, integrated, comprehensive, holistic approach to livestock handling. Likewise, low-stress livestock handling is referred to as a livestock-centered, behaviorally-correct, psychologically-oriented, ethical and humane method of working livestock which is based on mutual communication and understanding.

Cattle and goats are vigilant; they maintain a nearly constant, alert sense of the world around them. As stockmen (a term generally used in a non-gendered sense), we exist in behavioral relation to our livestock and can—with the right approach, mindset, position, and movements— leverage this relationship to guide animals through pasture, hold and settle them where needed, and usher them through corral and gate systems.

Handling livestock, Taylor reminded us throughout the workshop, requires neither coercion nor violence. What do cattle see? How do herds naturally want to move through space? By working to understand their perception and understanding of the world, we can engage with them psychologically rather than physically. Rather than force an animal to do what we want, stockmanship challenges us instead to read our animals. “The stock are never wrong,” stockman David Hart tells us, a reminder that as stewards of land and animals we owe our livestock patience and trust.

Various practitioners have diagrammed the principles of stockmanship in a variety of ways. Taylor’s approach highlights the importance of the human mind as the most material and controllable part of working with livestock. Cattle are highly susceptible to our energy, presence and intention. It is our foremost responsibility to control our attitude and emotions, which gives us an ability to care properly for our animals and, with time and practice, guide stock behavior and well-being. Stockmanship asks us to put our more heightened instincts aside to keep our livestock in their right, normal frame of mind.

After an in-depth lecture from Taylor and a lively discussion, the workshop group headed out to the corrals to spend some time with TomKat cattle. We ran through a series of exercises which allowed us to pinpoint when and how our presence and positioning impacted the behavior of the cattle. In small groups we filtered in and out of the arena, utilizing the tenets of pressure and relief to move the cattle with intention, helped along by guidance and feedback from Taylor, TomKat Ranch Small Ruminant Coordinator Stephanie Pittman, and Jade Barrett of Australia’s Konjuli Droughtmaster Stud.

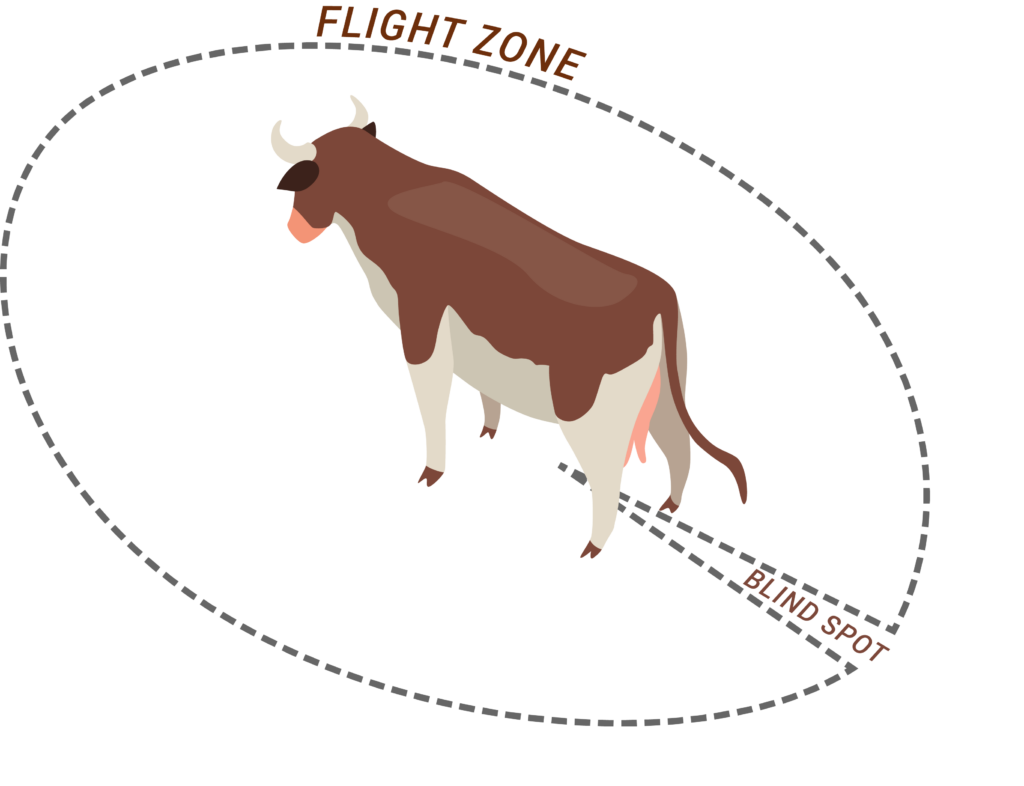

Impulse prompts us toward compelling our animals to act but throughout the workshop we were reminded that livestock actually learn from the release of pressure. The use of pressure and relief intersects with an understanding of an animal’s flight zone—the area within which they respond to the perceptible. A full, embodied understanding of maneuvering through the flight zone with pressure and relief is the means by which animals can be moved and handled without force.

Taylor challenged our group to ask ourselves why? Why we want to learn stockmanship, why it might improve the functioning of our own operations. Our answers will allow us to create personal understandings and applications of stockmanship for our own specific contexts.

Stockmanship and low-stress livestock handling are a demonstrable way to increase performance on both cattle ranches and dairy farms. Whit Hibbard points to a number of studies showing higher conception rates, better weight gain, increased immune function, and improved carcass quality correlated with low-stress practices—all increasing profitability without increasing inputs and making processing faster and easier. Agriculture is work, and the economics of raising livestock aren’t easy. The aforementioned studies show that stockmanship can directly improve profitability for livelihood farmers.

There’s a moral dimension as well. Non-human animals are as sentient and conscious as we are, as prone to pain and suffering. Stockmanship goes in hand with animal welfare and allows us to bypass the violence present in much of agriculture, which is, in contrast, human-centered and behaviorally-incorrect. Low-stress for the animals is, ultimately, low-stress for the human as well.

Taylor also centers safety in her approach, and takes great pride in creating a ranch environment that ensures the security of her family. Farmwork alongside large animals can be dangerous, but the preparation and concentration at the foundation of stockmanship helps minimize risk, especially in contained areas.

The principles laid out by Bud Williams and interpreted by Whit Hibbard hold true, but farming is always adaptive and iterative. Taylor reminded us to maintain a learner’s mindset, to keep asking questions, to continue building our relationship to stockmanship based on our own observations. Those of us in the workshop departed full of ideas and hungry to test them; ready to push ourselves and bring new principles and practices to our home farms and ranches. There was a vast appreciation for a supportive, generative site in which women could learn alongside one another. One declaration echoed repeatedly over our goodbyes: We felt empowered to go out and do good work.

There’s a magic to watching well-handled livestock. There is a wondrous cadence to seeing animals flow through space with calm and purpose. We’re proud to watch our animal herds closely each day, to read their needs and movements a little better every time we herd, to build a little bit more trust. We take great pride in using stockmanship to raise nutritious food, to graze our land, and to better exist in harmony with the natural world.

Resources:

Whit Hibbard’s Stockmanship Journal: Volume 1, Issue 1

Bud and Eunice William’s Stockmanship.com