Regenerative agriculture is increasingly being recognized as an effective tool for both mitigating and adapting to climate change.

What We’re Reading – A Synthesis of Ranch-Level Sustainability Indicators for Land Managers and to Communicate Across the US Beef Supply Chain

11/30/2021

By: Megan Shahan

Regenerative agriculture is increasingly being recognized as an effective tool for both mitigating and adapting to climate change. Sensitive to social, economic, and environmental contexts, regenerative practices can increase the soils’ capacity to sequester dangerous excesses of atmospheric carbon, retain water, and reduce the need for costly synthetic fertilizers and pesticides that are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Regenerative agriculture is increasingly being recognized as an effective tool for both mitigating and adapting to climate change. Sensitive to social, economic, and environmental contexts, regenerative practices can increase the soils’ capacity to sequester dangerous excesses of atmospheric carbon, retain water, and reduce the need for costly synthetic fertilizers and pesticides that are a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions.

Multiple efforts on international, federal, state and local levels acknowledge the need for increasing the practice of regenerative agriculture to build a more resilient and climate-smart food system. People around the globe are gaining awareness about the ways food production can either exacerbate or alleviate ecological, social, and economic pressures, including human health, the viability of small farms and ranches, and climate change. Numerous corporations have announced significant investments and initiatives designed to support and scale regenerative practices across their global supply chains, including some of the world’s largest food and agriculture companies.

In short, people are converging around the need for sustainable—and critically, regenerative— systems. But how are these complex concepts defined? And how are they measured?

A recent paper, A Synthesis of Ranch-Level Sustainability Indicators for Land Managers and to Communicate Across the US Beef Supply Chain, provides a first step to answer some of these questions for sustainable and regenerative ranching practices. The authors—a broad group of conservation, agricultural, academic, government, and scientific entities—evaluated 21 range and pastureland assessments to identify a core set of ecological, social, and economic indicators to help ranchers’ measure operational sustainability, inform adaptive management plans, and communicate relevant information across the supply chain.

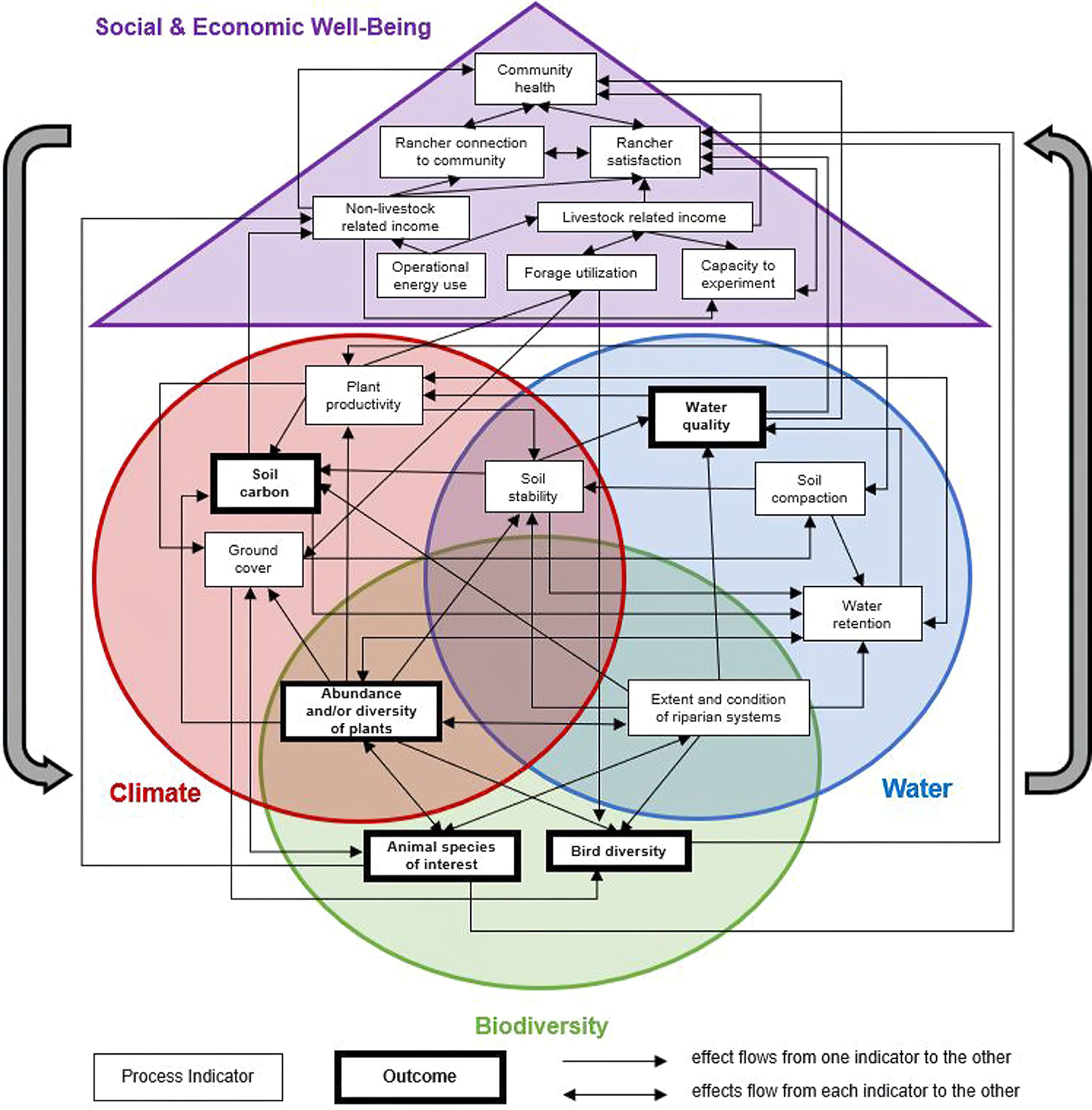

The 20 core indicators—12 ecological and 8 socioeconomic—were common amongst approaches, track change over time, and/or are of interest to companies or eaters. Core ranch-level sustainability indicators include: soil stability, water quality, diversity of native plants and birds, soil compaction, ground cover, plant productivity, rancher satisfaction with livelihood, capacity to experiment, and community health. These indicators are deeply interrelated (as the graphic below illustrates), representing the fact that sustainable and regenerative agriculture is a holistic approach to agricultural systems, guided by ecological, economic, and social goals.

Though there was general alignment on the importance of ecological indicators related to climate, water, and biodiversity, there was far less consensus on the socioeconomic indicators of ranch-level sustainability. Of the 21 approaches reviewed, all included ecological indicators, but economic and social indicators were present in only 11 and 5 of the assessments, respectively. The review “highlighted a gap in the way that rangeland sustainability is conceptualized and measured,” that is: economic and social sustainability are critical elements of real world sustainability, but their importance is not adequately represented in rangeland sustainability assessments.

Many challenges exist with agricultural data, such as: Who collects the data? Who bears the cost? How should the data be collected? Who has access to the data and how will it be used? In an effort to address some of these data challenges, the report notes the need for agreement on a simple and robust standardized protocol, including the development of region-specific benchmarks for ranchers or companies to track progress toward specific ecological outcomes.

Regenerative agriculture represents a paradigm shift in our relationships with food, nature, and people. Guided by key soil health principles—maximize soil cover, maximize living roots, maximize diversity, minimize soil disturbance, integrate livestock—it does not offer a “one size fits all” approach; it requires continual adaptation to one’s environmental, economic, and social context. And consistent monitoring, both on an individual ranch and on ranches across the country, can provide us with the necessary data and insights to learn and adapt, improving outcomes for ranchers, eaters, and the planet. Identifying common indicators of ranch-level ecological, economic, and social sustainability, as well as addressing common data issues, are critical elements needed to scale the practice of regenerative agriculture.