Many people ask our team at TomKat Ranch, “If regenerative agriculture is so great, why don’t more people do it?”. This is a great question!

What We’re Reading: Regenerating soil, regenerating soul: an integral approach to understanding agricultural transformation

07/28/2021

By: Kevin Alexander Watt

Many people ask our team at TomKat Ranch, “If regenerative agriculture is so great, why don’t more people do it?”. This is a great question!

Many people ask our team at TomKat Ranch, “If regenerative agriculture is so great, why don’t more people do it?”. This is a great question!

Regenerative agriculture (RA) creates many valuable social, economic, and environmental benefits for producers as well as the human and wild communities around them. Many producers who make the switch from industrial agriculture to RA enjoy improvements to their quality of life and lament that they didn’t switch sooner (for more on this, enjoy the video Soil Carbon Cowboys). However, RA is still far from being the dominant way people choose to grow food.

In June, Hannah Gosnell published an article in Sustainability Science exploring this question. Her piece “Regenerating soil, regenerating soul: an integral approach to understanding agricultural transformation” pursues a holistic understanding of why some producers in Australia were willing to switch to RA and others were not.

Complex Social, Ecologic, and Economic Decisions

Gosnell begins by pointing out that many of the current efforts to understand why some farmers switch to RA and others don’t are limited by over-simplifying what is, in fact, a highly personal and complex social, ecologic, and economic decision. She writes, “There is growing recognition of the need to integrate other important aspects of transformation with social-ecological systems thinking to more accurately understand and address [farmer/rancher transition to RA].” However, even with this growing recognition, many in the sustainability sciences have given little attention to researching the highly subjective and personal inner lives of farmers and ranchers.

4 Considerations for Adopting Regenerative Agriculture

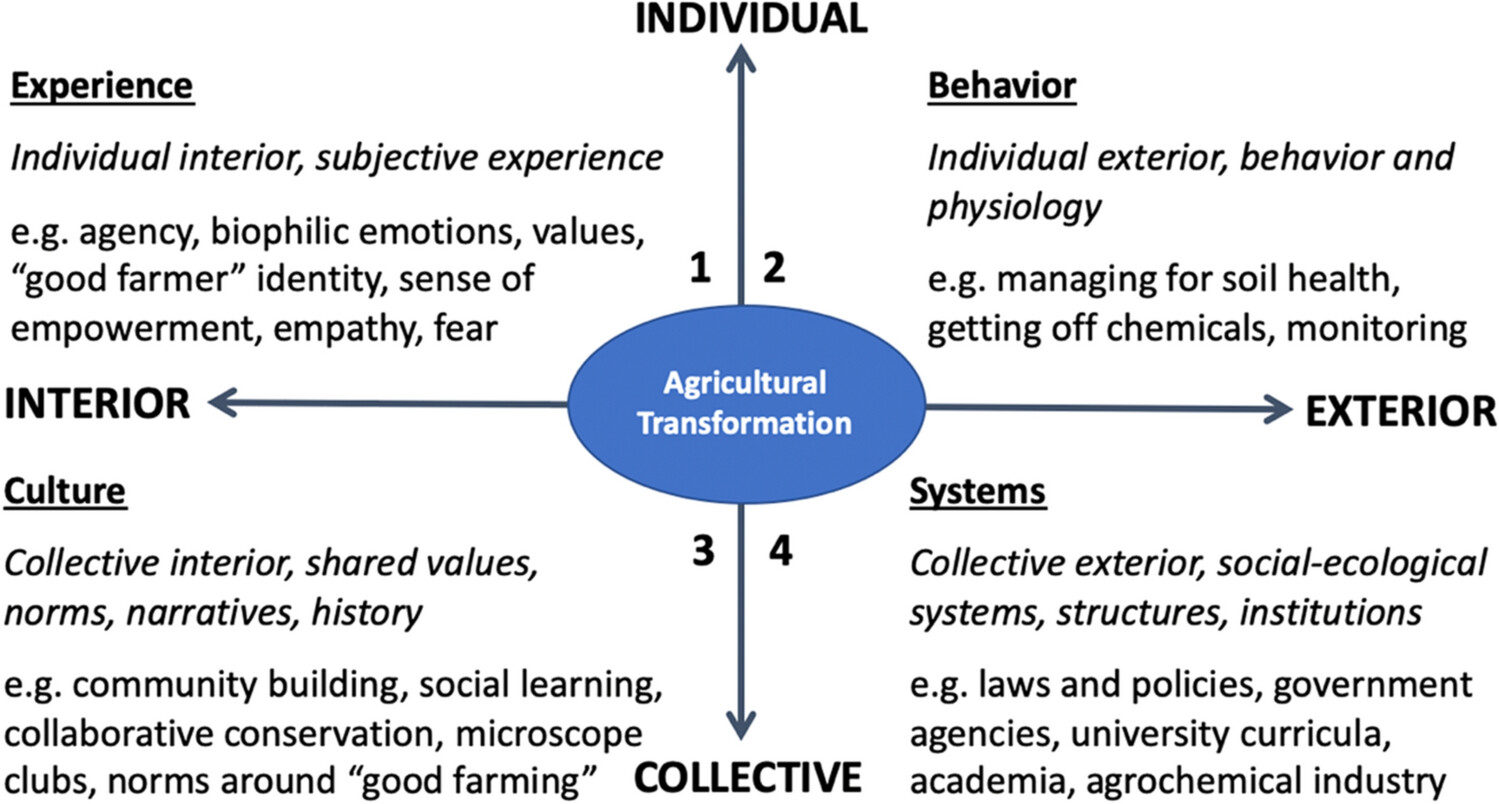

Gosnell’s article seeks to address this shortcoming by exploring the question of farmer adoption across four areas: personal experience, culture, behavior, and systems (see figure below). Noting that there are “a myriad of entry points to a consideration of levers for the agricultural transformation associated with [the inner lives of farmers/ranchers]” she focuses her attention in this paper on exploring how these four areas interact with one potential entry point, namely “farmers’ experiences with agrochemicals and the microbiome.”

Before diving into how agricultural producers make the shift to RA, Gosnell first articulates the foundational differences between how regenerative and industrial growers see their relationship to the land and ecosystems they inhabit. She writes:

Regenerative farmers “see” soil differently, as a biological system rather than a chemical reservoir and this is why they work to support subterranean life rather than kill and replace it, fostering a “sub-terranean symbiosis” between mycorrhizal fungi and plants to bring soil back to life. They also think differently about water. Drought is not just determined by what falls from the sky, it has to do with what is in the soil and whether the ground can hold water (Montgomery 2017). Rather than reactively depending on precipitation, regenerative farmers proactively manage landscape and soil processes to improve water storage and availability….helping land retain all the rainfall it receives (Yeomans 1954; Doherty and Jeeves 2016)…

Australian farmer Charles Massy (2017, 391) observes that “the leading regenerative farmers work with and not against nature: they seek to enhance her uniquely complex functions, nuances, and directions—even when they don’t fully understand them.” Regenerative farmers enjoy a different relationship with their livestock that involves “low stress” animal husbandry and learning from their “nutritional wisdom” (Provenza 2018).

So how do agricultural producers make this crucial shift in thinking?

Negative Experiences with the Industrial Food System

Gosnell posits that one important entry point is the negative experiences many industrial producers have with agrichemicals. Many producers she spoke to who had transitioned to RA shared that the “slow realization that the agrochemicals [they] relied upon were not working as well as they had in the past while becoming increasingly unaffordable” was a pivotal moment in their switch to RA. Gosnell highlights that these negative experiences are pivotal and catalytic because they often go beyond a purely intellectual realization and include a strong emotional experience as well. She quotes a regenerative consultant/educator she interviewed who says, “The process of change has to start with an emotional response. “I’m either happy with what I’m doing or I’m not happy.” It has to start with some discontent and part of the process is not just working out where your discontents are but working out where you want to move towards that would make you content.”

Social Risks

Another important entry point Gosnell explores focuses on social elements. Farmers and ranchers often perceive huge social risks to changing their production methods as they fear it may alienate them from their communities. A farmer interviewed by Gosnell shares, “There was a lot of peer pressure on you to toe the line in what they were doing in that district. “You need to be doing the same things we’re all doing, because we don’t like what you’re doing,” is pretty well what you get. “We’re uncomfortable that you’re grazing that way.” And anger. Like, I had farmers who were angry. What I was doing had nothing to do with their property, but they were angry that I was doing a certain thing.” In addition to potential social isolation, farmers and ranchers who adopt RA also often find that the transition can also be made more difficult by the lack of technical assistance provided by government services that are often tailored to only serve practitioners of industrial agriculture.

Supportive Social Networks

Accessible positive social networks help to alleviate many of these problems by providing meaningful peer-to-peer support and knowledge transfer and can be crucial for helping producers create a new positive social identity as regenerative farmers/ranchers. As an example, Gosnell discussed the value of local “Microscope Groups” where producers organize field trips to each other’s operations to discuss land and management and look at microscopic soil microbes together. For many these meetings are transformative. One participant noted “And it’s like holy s#*#, in that little pile of stuff there really are a lot of living things. They can see it and they just can’t believe what they look like up close and they’ve never thought about it before in that way.” The above-quoted farmer continues. “[Participants in the groups] get a little high off of knowing that their peers respect what they’re doing. And sharing techniques and information, how do I achieve better results.”

CALL TO ACTION

Ultimately, Gosnell’s article is an excellent call to action for taking a more holistic approach when exploring the many factors that can influence farmers and ranchers transitioning to RA. As so many regenerative researchers and advocates have demonstrated, this transition can be hugely beneficial for producers and their surrounding communities alike. However, more information or new studies do not address the fact that the change to regenerative agriculture can be frightening and alienating for many producers. We at TomKat Ranch hope that this article, and hopefully many others that will follow in its footsteps, will show that a transition to regenerative agriculture must not only be scientific and data-driven, but also empathetic, patient, and committed to building trusting and supportive relationships.

To read more of Hanna Gosnell’s piece, please click here for the article.