Bale Grazing – Stewardship During Drought to Grow Soil Health

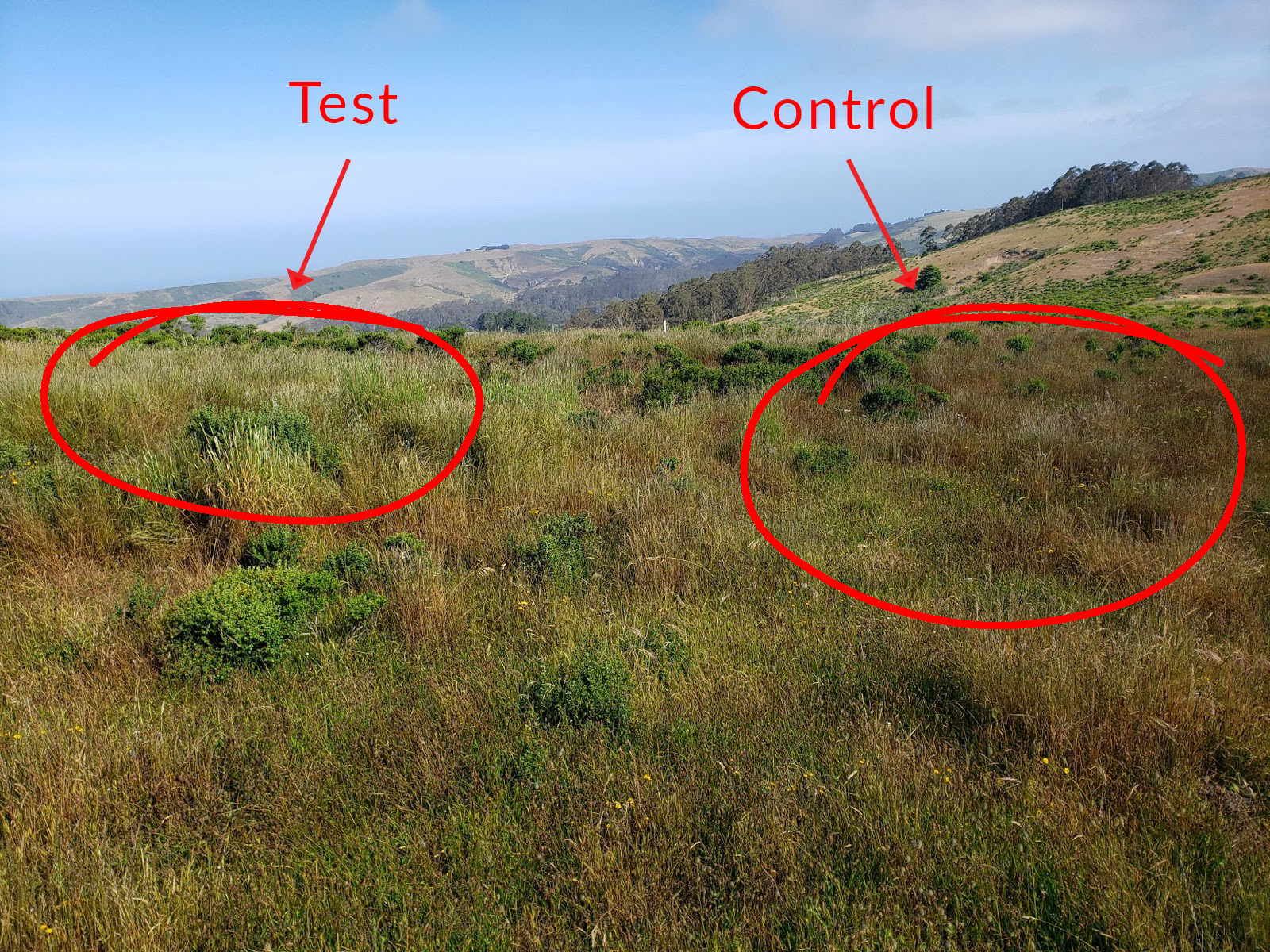

Composite aerial view of Lone Tree Hill pasture showing bale grazing test area results. Early into the trial, the test areas are already ‘greening-up’ suggesting high biological activity and greater water retention than the surrounding “control” areas. March, 2021

06/18/2021

By: Mark Biaggi and Celia Hoffman

Background on bale grazing:

When fresh grass is not available in the winter across much of the US and Canada, ranchers feed cattle big bales (1,000 lbs+) of hay either in a feeder or rolled out randomly across their pastures. Decomposing uneaten hay (some would call it “wasted” because it didn’t contribute to animal performance) combined with manure and urine can boost the soil microbial community and provide beneficial biomass. This “wasted” groundcover sustains microbes when Spring arrives leading to healthier soils, improved infiltration and retention of snow-melt and rainwater, and increased land productivity.

Given all of the benefits, this is an amazingly efficient and effective way to feed both livestock and microbes and puts this practice squarely in the toolbox of options for regenerative ranchers. As is often the case with planned grazing, organized and planned bale grazing has shown incredible results for both livestock and growing healthier and more resilient soils. Unfortunately, many practitioners do not fully recognize the benefits and so choose to place the hay bales in locations based on convenience more than potential impact.

Example of bale grazing from Beef Magazine: Bale grazing: An option for easier winter feeding – Copyright, Beef Magazine

Five years ago, in the winter at TomKat Ranch, we tried bale feeding as a supplement but had not selected the right locations or spread the bales which resulted in negative results. We had placed the bales, and therefore the cattle, in concentrated areas on wet clay soils which inevitably led to soil compaction from the cattle’s hooves, or “pugging.” Soil compaction is one of the more detrimental impacts on soil health and can take years to heal. During the intervening years, we researched other bale grazing methods and shifted our approach. Here are three things we learned about how best to apply this practice:

- Focus on the soil. Soil is the foundation of the pasture and as such, we need to ensure all practices build soil life (we think about using the hay to feed microbes and restore soil health)

- *Prevent damage. By feeding bales when the ground is hard (in our climate that means in the fall before the rain), we can avoid pugging.

- Save ungrazed pasture. By planning appropriately we can stockpile (save) enough ungrazed pasture to let the cattle spread out to graze during times when the soil is saturated and also susceptible to pugging.

*CORRECTION: In our original post, we included the word “not” after the word “By” when alluding to the best time to bale feed. That was in error and it now reads correctly.

Photo May 4, 2017 at Lone Tree Hill Pasture – a North facing pasture where we fed cattle in the winter of 2016-2017. A few positive impacts can be seen but overall there is too much “wasted hay” that didn’t break down into food for the soil and too much compaction.

Last fall, in the face of yet another dry winter, limited projected forage production, and less than optimal acres of grass due to the previous dry year, TomKat Ranch (along with every grassland livestock producer in the area) had to make the decision to destock or feed supplemental hay. As always, there are positive and negative long-term consequences to consider. Most often, destocking is considered the best decision to protect a ranch’s fields, soil, and economics. In our case, however, the long-term strategy of our learning laboratory is to protect the soil and improve water infiltration and absorption rates for when the rain reappears … So we decided not to de-stock and instead set out to use our herd to address the question: can hay and the practice of bale grazing rebuild the soil during dry years without destroying the existing pasture?

What we’re doing at TomKat Ranch:

We selected Lone Tree Hill, a 15-acre field with low productivity located away from a main waterway (to guard against nutrient runoff) for the bale grazing trial. This pasture was tilled and farmed for decades before the current ownership and the last hay crop was harvested in 2010. The years of farming heavily compacted the clay soils and left behind minimally productive native perennial grass and low-yielding annual grasses.

For 28 days starting in late November 2020, we spread a combination of alfalfa hay and milo bales over a limited area to feed cows and concentrate the litter and hoof disturbance. Every third day, the cows moved to a new section of the field and were fed fresh bales to make sure they had access to fresh feed and a new space to spread manure and urine and hoof impact equally around the trial area. The cows covered the entire field throughout the month, consumed 92,727 pounds of hay, and spread on average 4,945 pounds of manure per acre.

A month after the cows left the field, we sprayed both the control and test areas with a mix of Vermicast, humates, kelp, and liquid calcium to enhance the breakdown of the manure and stimulate microbial growth to help move the plant community towards more grasses, forbs, and legumes.

Results so far:

To be clear, we set up the bale grazing trial on Lone Tree Hill not as a scientific trial, but as a safe-to-fail study using observation as the key measuring tool. We considered the areas where the big bales were placed as test plots while any areas outside were control plots.

After the cows’ departed, we checked the field regularly for signs of growth and change. In late February, two months after the cows had left, there were high densities of thick, 8-10” tall, green grass-covered areas where the bales had been placed (the tests). However, cow manure pats remained numerous and had not broken down, possibly an indicator of low microbial activity. Additionally, Brix test results (a measure of the photosynthetic capacity and quality of the plant-based on its carbohydrate content) were a low 3-4 in the test areas, compared to 6-7 in the control area. Ideally, Brix ratings for cattle grazing should be in the 10-14 range.

In March, we moved the cows back into the field with both control and test areas to observe their preference. At the time, they disliked the feed grown across the entire field and were not interested in eating except for a few areas of the test sample, so we moved them out within hours. Based on the low Brix results—and the cow’s lack of interest in the test plots—we concluded that the lack of rain had likely slowed the breakdown of the manure and urine resulting in forage that “appeared” good but was actually “offensive” to the cattle—a natural phenomenon where cattle will not readily graze near the manure of the same species.

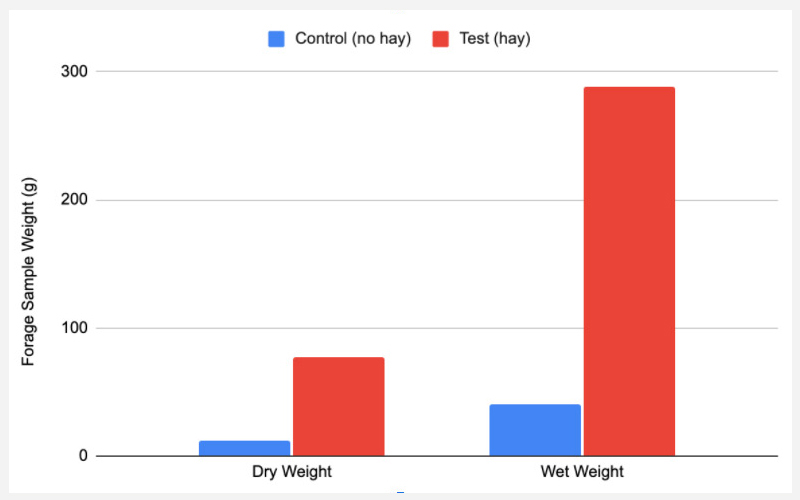

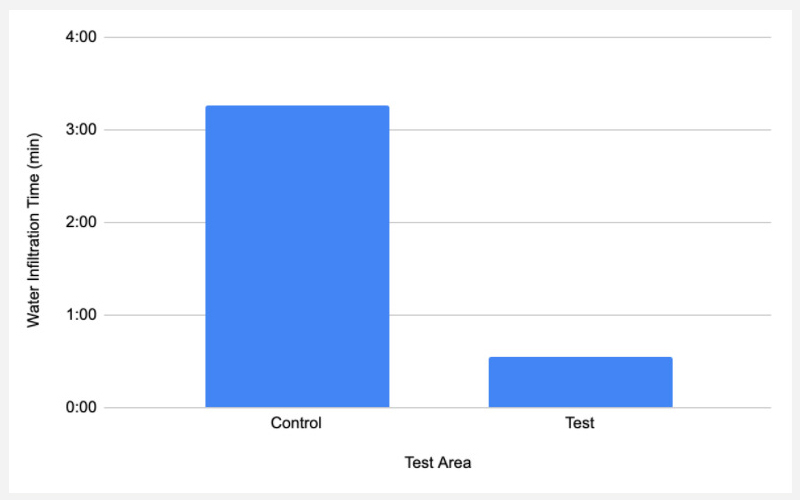

By mid-April, the bale grazed area supported forage still in a vegetative state (growing) while the grasses in the control areas had moved into reproductive stages (energy diverted from growing to seed production). Initial results from soil samples showed little difference between test and control. However, the biomass and water infiltration tests showed large differences as seen in Figures 1 and 2 respectively.

Figure 1: This figure shows the average dry and wet weights of twelve biomass samples taken per treatment across four sections of Lone Tree Hill – a ~630% increase in weight in both cases.

Figure 2: This figure shows the average water infiltration time of four replicates per treatment in each of four sections of the field. The test sample showed a 658% infiltration improvement from the control sample.

The average biomass (3 weeks dry weight) increased from 0.6 tons/acre to 3.7 tons/acre, a 630% increase! Water infiltration had an average improvement of 658%! We think the significant changes in biomass production and water infiltration support expanding the bale grazing trial to additional acres under similar conditions to see if this method of grazing can show similar benefits at scale.

Next Steps

We will bring cows back to Lone Tree Hill in late summer 2021, allow for maximum manure decomposition before regrazing, and observe cattle grazing patterns to see if they are showing a preference for the grass of either the test or control site.

In fall 2021, we will try the same practices on a larger scale in different areas of the ranch. Given increasingly dry conditions—our second rainfall year with less than 50% of average—we wish to test the degree to which biological inputs can heal heavily farmed soils and prepare fields to capture water more efficiently. The critical elements of this strategy are soil cover (layer of litter) to protect the soil from dehydration, promote water infiltration, provide food for microbial life (manure, urine, and litter), and prevent soil compaction by diffusing hoof impact.

At this point in the drought conditions, we see bale grazing as a long-term investment (given the time it takes to see benefits to the soil and forage). We are excited to continue to learn about the possible benefits of using bale grazing as a tool for soil building and as a reaction to drought years. We look forward to continuing to share our results in the hope that other grazers can learn from our mistakes as well as our successes.

Photo Story of the current project

The following photos show various stages of this trial (December 2020 – June 2021).

December 2020 Trial Plot – This photo is after the cows were fed the bales. Soil is covered with a thick layer of “wasted hay” mixed with manure and urine that will feed the microbes.

April 2021 – Same location, 100 days after grazing and some rain.

April 2021 Control plot – Soil is obviously visible even after winter rains.

April 2021 Test Plot – Grass completely covering the soil. Water infiltration appears improved resulting in robust growth.

June 2021 – Test (left side) shows north face still green and growing vs Control (right side) that has less growth that’s drying out sooner.

June 2021 – Growing season is slowing. Forage will be ‘stockpiled’ for Fall grazing.